In the late 1800s in West Virginia, a railroad worker named John Henry, built like Hercules, entered into a hammering competition with a newly invented steam-powered drilling machine.

John Henry won.

The effort, though, killed him, and he died at the scene in his wife’s arms.

The story turned into a song. More than 200 versions of it exist.

It could be merely folklore, this tale. But it turns out to be, most likely, quite real.

John Henry, who died with a hammer in his hand, was a 5-foot 1-inch Black man, on loan from the Virginia state penitentiary.

***

As I’ve mentioned before, as a very young child I listened incessantly to an album called America on the Move, which featured folk songs about trains and railroads. I was particularly obsessed with a tune called “John Henry”:

When John Henry was a little baby

Sittin’ on his daddy’s knee

He said, “The Big Bend Tunnel on the C&O Road

And the hammer’s gonna be the death of me, Lord,

The hammer’s gonna be the death of me.”

Now the captain said to John Henry,“

Gonna bring me a steam drill ’round.

Gonna take that steam drill out on the job.

Gonna whop that steel on down, Lord.

Whop that steel on down.”

Well, John Henry said to his shaker,

“Man, why don’t you sing?

I’m throwin’ 12 pounds from my hip on down.

Just listen to that cold steel ring, Lord.

Listen to that cold steel ring.”

Well, John Henry swung the hammer over his head.

He brought the hammer down to the ground.

A man in Chattanooga 200 miles away

Said, “Listen to that rumblin’ sound, Lord.

Listen to that rumblin’ sound.”

Now, the man who invented the steam drill

Thought he was mighty fine.

Well, John Henry drove about 15 feet

And the steam drill only made 9, Lord,

The steam drill only made 9.

John Henry said to his shaker,

“Man, why don’t you pray,

’Cause if I miss with this 9-pound hammer

Why, tomorrow be my buryin’ day, Lord.

Tomorrow be my buryin’ day.”

Oh, they took John Henry to the graveyard

And they buried him in the hot sand.

And every locomotive come rollin’ by

Says, “There lies a steel-drivin’ man, Lord.

There lies a steel-drivin’ man.”

Just about every singer who represents American culture has covered this song – folkies, rockers, and troubadours from Pete Seeger to Harry Belafonte to Johnny Cash to Bruce Springsteen.

The most rollicking version is Springsteen’s Seeger Sessions cut. Check it out here and get ready to rollick:

***

The endless permutations of “John Henry” lyrics reflect the multiple theories about the man himself. His story may be 100 percent fact or 100 percent folk tale. But I believe it’s a little bit of both. I think it emerged from truth and picked up scraps of mythology as it rolled down the track.

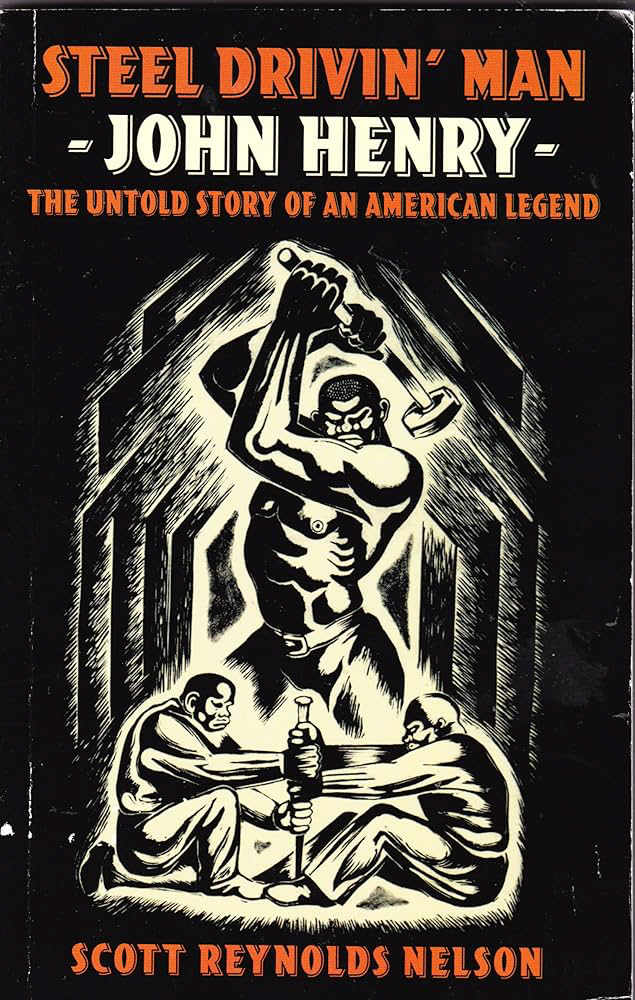

Historian and professor Scott Reynolds Nelson of the University of Georgia may have uncovered much of the real story. In his 2006 book Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend, he documents the existence of a 19-year-old Black man named John William Henry imprisoned at Richmond’s Virginia Penitentiary in 1866 – one year after the end of the Civil War. That prisoner had been arrested for shoplifting but convicted of burglary and sentenced to 10 years after an unjust trial. Now, I’m a very strict law-and-order gal, but a decade in prison for shoplifting seems like a wildly disproportionate punishment.

Then, partway into his sentence, John Henry was assigned to private contractors to do railroad work.

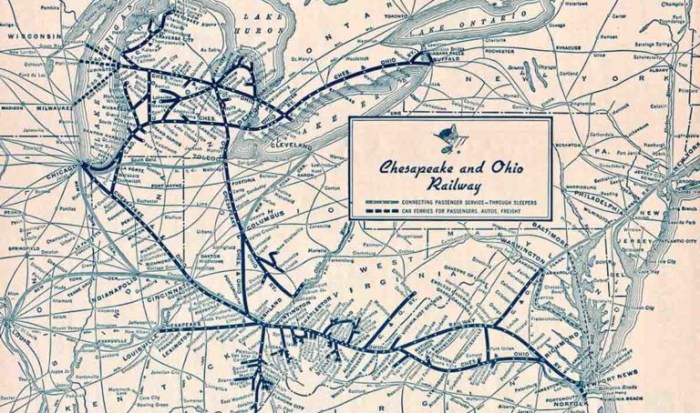

During Reconstruction after the Civil War, constructing a mammoth railroad system seemed like a perfect way to reunite a fractured country. The C&O (Chesapeake and Ohio) Railway was being built from Richmond, Virginia over the Allegheny Mountains to the Ohio River in the new state of West Virginia – a critical first link in a dream of connecting the south to the north. (It would eventually reach all the way to Chicago.) Collis P. Huntington, one of the Big Four railroad magnates, was called in to lead the effort. And he needed labor – lots of it.

Freed former slaves began signing on in droves to work for the railroads, even though they labored in a lonely, cramped, dangerous, and nearly inhospitable environment. It was, I suppose, at least a notch above slavery. But the companies needed even more workers, so they commonly turned to convict leasing. They “rented” prisoners at an extremely low price but had no incentive to treat these new “employees” well. More than 200 prisoners were leased from the VA State Penitentiary in the late 1860s.

John Henry’s 10-year prison sentence – beyond being an unusually harsh punishment at the time – was in actuality a death sentence, according to Nelson, because very few men survived 10 years at the Virgina Penitentiary under its filthy conditions. So it may have seemed like good fortune to Mr. Henry, initially, that he was sent out to work on the C&O railroad under his convict labor lease deal.

And the good fortune to the railroad? A prisoner’s lease cost only 25 cents a day.

***

John Henry was assigned to a team that worked on drilling tunnels through miles of hard granite. Even though he seems to stand 7 feet tall in the public’s imagination, amazingly his prison records list him as 5 feet 1 inch, which, if true, actually would have suited him for tunnel work.

According to the song, John Henry was a steel driver – a laborer who repeatedly hammered hefty spikes into rocks. A steel driver would work alongside a “shaker” who held the spikes in place and rotated them after each blow. Once the hole was sufficiently large, it would be filled with explosives by a “blaster” and more of the tunnel would be blown away. Initially, before the use of nitroglycerin, the holes were fist-sized and filled with gunpowder.

The men worked 12 hours at a stretch, but the mountains were hard shale, and the work produced only a few inches of tunnel each day. Imagine how dispiriting that must have been.

(By the way, the shaker’s side-to-side movement of the drill bit between hammer blows was called “rocking”; twisting the bit was called “rolling.” So “rock and roll,” according to Nelson, was originally an old mining term before it evolved into a euphemism for sex and then the name for simple chords and a driving beat.)

***

One of the most harrowing tasks for the C&O steel drivers was blasting a tunnel through Big Bend Mountain west of Talcott in West Virginia. The mountain was more than a mile thick, and it took 1,000 men three years to finish it in 1873. During that time, falling rock killed many a man and many a mule.

Then along came the invention of a new steam-powered drill. Huntington needed to get the tunnels blasted more quickly in order to acquire the rights to the entire rail line. He’d already gotten the cheap labor; now he thought the steel drill would be the answer to his production problems because it wouldn’t rely on human muscle for the hammering.

But reality would prove that the machine operated more slowly than its hype and had a tendency to get clogged up by the powdered sediment.

So somebody dreamed up the idea of a competition between man and machine.

John Henry, by then renowned as the world’s best steel driver, was matched against the new drill at Big Bend. (Or so the legend goes. There’s some evidence, and Nelson believes, that the contest actually occurred at the Lewis Tunnel, about 40 or 50 miles away.) The competition lasted through the night and into the next day. John Henry, with his powerful muscles and his 12-pound hammer, won the contest, allegedly driving 15 feet while the machine could manage only 9.

The story goes that John Henry immediately succumbed from exhaustion. It may instead have been a heart attack, a stroke, or some other mining-related condition like acute silicosis, a lung disease (sometimes mislabeled as “consumption”) caused by the inhalation of small pieces of crystalline rock produced by the splintering of granite. The disease was so common among the tunnel workers that most of them died less than 10 years after they started working on the rocks.

John Henry’s wife, Polly Ann, was allegedly at his side when he died, and he left behind a baby.

***

The lyrics in one version of the song (“They took John Henry to the white house/And buried him in the sand”) were somewhat of a mystery until Nelson immersed himself in the research. After discovering an old Virginia Penitentiary postcard, Nelson concluded that the “white house” is a reference to a ditch behind a white building at the prison where hundreds of unmarked graves of men 18–30 years old were discovered about 30 years ago, and where locomotives “come rollin’ by.” There’s a train in the postcard.

The C&O Railroad was legally bound to ultimately send all prisoners back to the penitentiary – even those who died on the job.

Three hundred Black convicts died while working on the C&O and were shipped back to Richmond.

No further prison records exist for John Henry after he was sent out, so it’s likely that he didn’t make it back alive.

***

And what about the song itself? Nelson says that it started out as a “hammer song” – a tune sung by workers as they labored on the rail lines. It was about backbone and guts. Hammer songs were sung very slowly so that workers would let up a bit and avoid death by exertion.

“John Henry” would later become a blues lament when the Great Migration that started in the early 1900s brought Blacks out of the south and into New York and Chicago in search of jobs.

But it wasn’t necessarily only about race. Fiddlin’ John Carson, a white country singer, recorded it in 1924; he’d been a textile mill worker and Nelson thinks the song spoke to overworked laborers in general who were “fighting the machine.”

Then “eventually the Communist Party takes it up,” says Nelson. “Charles Seeger [father of folk singer Pete Seeger] is responsible. . . . He sees it as about fighting against the capitalist machine. . . . It was used to organize Black workers. John Henry becomes this sort of poster boy who becomes the true American hero who fights against capitalism and ultimately is destroyed.”

Songwriters are our “enduring historians.”* Their works, passed down through generations, preserve the actual experiences of people whose stories might otherwise be censored or bent into a distorted narrative. The songs keep us from forgetting.

***

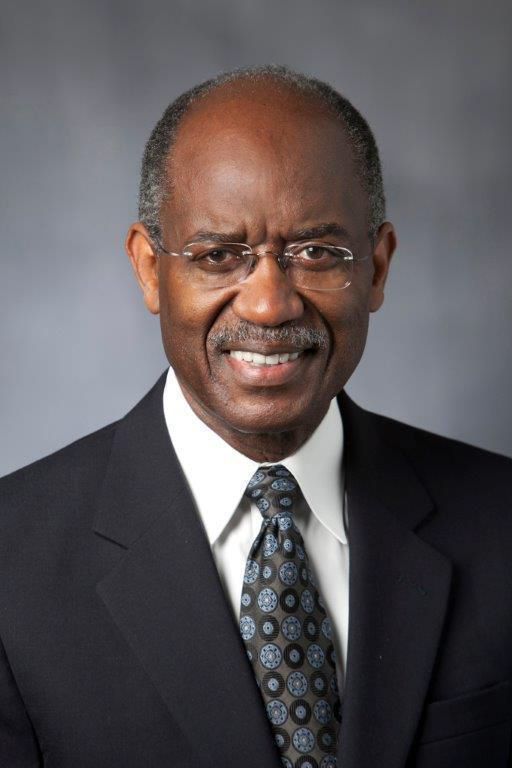

In the 1970s, epidemiologist Sherman James – now an emeritus professor of public policy at Duke University – was researching racial health disparities when he met a Black man who’d been born into a poor sharecropper family. The man had educated himself and acquired 75 acres of farmland, but he suffered from severe hypertension and peptic ulcers by the time was in his fifties. His name was, interestingly enough, John Henry Martin.

Dr. James eventually developed a concept called “John Henryism,” evoking both Mr. Martin and the John Henry of lore. The hypothesis was that chronic exposure to social stresses like intense bigotry can force people to expend such high levels of effort to cope with the stress that they suffer premature physiological costs. Exploitation and discrimination, Dr. James theorized, often compel people to go to superhuman lengths to prove their worth – working much harder than expected and exhibiting ferocious commitment to their jobs.

***

Some folk heroes are real, like Joe Hill, Calamity Jane, Johnny Appleseed, John Brown, Casey Jones, Spartacus.

Some – like Robin Hood – are debatable.

And others are clearly imagined.

But their commonality is that they’re generally not appointed leaders. They’re regular people, often from humble beginnings, who rise to the occasion when confronted with injustice.

On its basic level, John Henry’s story is just about a man with strength that few men possess. He’s like the fabled Paul Bunyan – the gigantic lumberjack whose likeness has inspired many a statue, along with his colossal blue ox “Babe.” A superhero, if you will. Simple as that.

Assuming Nelson’s research is relevant, though, John Henry’s life also reflects the consequences of the abuse that many accused and convicted Black men had to endure after the Civil War.

On an even larger scale, the story is about the potential effects of careless capitalism on the working class when employers without a conscience rely on hubris and greed and neglect the heart. The railroad barons, for example, would exploit former slaves, Chinese immigrants, and other hard-working laborers for years.

I believe wholeheartedly in capitalism, but as with everything else, it has the potential to veer out of control.

So is the story of John Henry uplifting or distressing? After all, John Henry’s victory proved also to be his demise.

Well, I want it to be a hopeful story.

I want to believe in a world in which the unique qualities of human beings will always transcend technology. That’s a fragile notion that could capsize in the oncoming AI wave, but let’s hope our greater angels keep us afloat.

I also want to believe in that moment when a little guy stands up to the big guy with all the power – and wins.

And because today’s world has grown increasingly disturbing, maybe I’m yearning for something fantastical that can save us from ourselves. I want to believe that it’s entirely possible.

***

At some point in the early 1870s, a huge rockfall in the Big Bend Tunnel killed an entire train crew, prompting the C&O to begin lining the inside of the tunnel with brick.

During that effort – which took 10 years and more than 6 million bricks – workers claimed to have seen John Henry’s ghost and heard the cold steel ring of his hammer.

Well every Monday morning

When the bluebirds begin to sing

You can hear John Henry a mile or more

You can hear John Henry’s hammer ring, Lord, Lord

You can hear John Henry’s hammer ring

Anything is possible.

***

* My dentist Dr. J.H. recently used this phrase about storytellers in a piece she wrote about her family history, and I am shamelessly cribbing it.

***

COMMENTERS, PLEASE NOTE: WordPress is no longer supporting my particular page type and doesn’t seem to be asking commenters for their names, so everyone is identified as “Anonymous.” If you’re commenting (which I love!), please leave your name if you’d like me to know who you are!

***

Due to popular demand, I am including, at the end of each blog post, the latest random diary entries that I’ve been posting on Facebook for “Throwback Thursday.” These are all taken absolutely verbatim from the lengthy diaries I kept between 1970 and 1987.

April 19, 1975 [age 19]:

“I decided that I’m going to quit [Rexall Drugs] on July 16th, and it took me all day long to get up the courage to let [my boss] Mr. Jordahl know of my plans. I finally decided, when I was doing the ring-out and he was about to leave, but even then I put it off, my heart beat a hundred miles a minute and my throat throbbed and got heavy and I began to sweat like a pig, I mean I could SMELL myself, so when I calmed down I forced myself to blurt, ‘James Lick [High School] has given me an offer for next year which I couldn’t refuse,’ and I emphasized that it wasn’t personal. He looked sad at first, said [another employee] was leaving, too, and that he wanted to move to Seattle. I felt so sorry for him. But then he said something like, ‘Maybe we won’t be able to accommodate you till the 15th, if we find someone sooner,” and I thought of how many years I’d been there and my face grew hot with anger.”

April 20, 1975 [age 19]:

“I’m worried about my social limitations and that living in the dorms will be hell on me in the fall. But instead of dwelling on that, I went to the liquor store to see [my friend] Morris and to exchange enthusiasms about the summer.”

April 28, 1975 [age 19]:

“I’m so bright-eyed about going back to school in the fall! [My brother] Marc brought me a new schedule of classes and there were all kinds of neat classes I’m interested in: ‘Backpacking,’ ‘Autobiography Writing,’ ‘James Joyce,’ and ‘Narcotics Abuse.’ ”

April 29, 1975 [age 19]:

“Hay fever season is going to be bad this year – today I sneezed continuously all the way home from Lick [High School]. Nonstop. So at work I sniffled and blew until Ola [the pharmacist] shoved some Actifed at me. That medication just mellows me out and mixes me up.”

May 3, 1975 [age 19]:

“[One of the high school teachers I worked with] told me she was really unhappy yesterday and I really think I know what her deep problem is – and this is PURE conjecture. I think she may be a homosexual who is losing her best friend (they’re roommates) to a man, and she is suddenly seeing that life for her does not hold the same promise that it does for everyone else. Why does God make people who have to feel like outcasts?? ‘What is there to live for?’ she said to me. And I felt like jumping up and screaming, ‘Well, look at me! I work 50 hours a week, I don’t have anyone, I’m neurotically introverted, I’m lonely . . . . So what do I live for? For the Moody Blues, good food, blue jeans, Santa Cruz, red sunsets, pancake breakfasts, Jack Kerouac, my guitar, empty streets at midnight – all the LITTLE things!’ ”

May 12, 1975 [age 19]:

“I went down to play softball with our neighborhood gang tonight, and of the uncomfortable results – namely, mosquito bites and terrible hay fever – only one was sufficient to cause me to grieve: I’ve lost my touch. Out of approximately 9 times at bat I got only one hit. The rest of my efforts dribbled out to the pitcher. I used to be GREAT! I could hit [my friend] Ted’s basketball hoop from any corner, I could outrun anyone in touch football, I could snag any ball that came within 40 feet of me at first base. And now – it’s disgusting. Humiliating, mostly. The demise of my youth. And the decline of a neighborhood hero.”

They told this John Henry story on a tv show called “Man VS History”. Only on the history channel. True story. They even talked about Johnny Appleseed and Paul Bunyan. P.B was fictional, but guys like J. Appleseed, John Henry, Casey Jones, and Davy Crockett were real people.

LikeLike

Thanks, Paula. A fascinating story in itself, maybe, but you make it especially readable and engaging in your version of it. It’s you who bring John Henry to life.

Maryl

LikeLike

Thank you, Marilena! That means a lot coming from you!

LikeLike

Thank you, Neil! It really was music that got me interested in John Henry — the folk song I listened to incessantly as a child and then Springsteen’s cover on the “Seeger Sessions” CD. I’m also a rail fan, so I’m sure that helped as well. Happy Holidays to you!

LikeLike

Paula, this is a terrific essay. As with many of your pieces, I’m impressed by the amount of research you do. How did you get interested in John Henry initially?

LikeLike

Thank you, Neil! It really was music that got me interested in John Henry — the folk song I listened to incessantly as a child and then Springsteen’s cover on the “Seeger Sessions” CD. I’m also a rail fan, so I’m sure that helped as well. Happy Holidays to you!

LikeLiked by 1 person