My Italian aunt and uncle owned exactly two books: Myra Breckinridge and Everything But Money.

You could find those two paperbacks on the living room end table next to TV Guide and Reader’s Digest and the bowl of toffee candies.

Myra Breckinridge was, of all things, a 1968 Gore Vidal satirical novel that touched on themes like unconventional sexual practices. Why my puritanical aunt Nini and my uncle Ray owned that book will forever be a huge mystery to me. (Of course, as a kid I used to sneak-read it when everyone else was out of the room.)

The other book, though, was its polar opposite. Everything But Money, by comedian Sam Levenson, was a decidedly G-rated, heartwarming, and hilarious accounting of Levenson’s youth in New York with his seven siblings and Jewish refugee parents in the early 1900s. It’s a lifelong favorite of mine, and I read it again this summer.

Jewish humor appeals to me partially because it turns adversity into comedy. Sometimes it pokes good-hearted fun at the culture, but mainly it’s all about kvetching. I know I’m painting an entire group with a broad brush, but in general I like hanging out with Jewish people because I always have a good time. Had I been born a couple of decades earlier, I probably would have vacationed in the Catskills.

My father loved the satirical songwriters Tom Lehrer and Allan Sherman when we were kids. He’d walk around the house belting out “National Brotherhood Week” and “Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh.” Lehrer and Sherman are Jews. Maybe that’s where I learned more about the humor.

But it all started with Sam Levenson.

***

From the 1880s through the 1920s, huge numbers of Jews and Italians emigrated from Europe to the United States during the “New Immigration” period. The Italians were fleeing a politically chaotic country and the Jews were fleeing anti-Semitic laws and organized massacres in Russia. Both groups left behind crushing poverty in hopes of taking advantage of American economic opportunity.

The Jewish population in New York City alone grew from 80,000 in 1880 to 1.5 million in 1920. Many of these immigrants settled on the Lower East Side or in Brooklyn. According to the Jewish Women’s Archive, “They lived in tenement housing and worked alongside other Eastern and Southern European immigrants in the area’s sweatshops and textile factories. . . . Though Jewish immigrants in this period faced difficult conditions in housing and work, their experiences in America were still an improvement over their lives in Eastern Europe. In America, they were able to find jobs, even if those jobs involved harsh conditions and low pay. Immigrants could also move freely across the country and practice Judaism openly, which was not always allowed in their countries of origin.

“The tenements Jewish immigrants lived in when they arrived in US cities were large, crowded apartment buildings built to house the multitude of workers immigrating to the US in the late 19th century. They were characterized by lack of light, air, and sanitation. Families often could not afford an entire apartment to themselves and would take in boarders to help pay the rent. Even with this additional income, in many families, every member had to work, even the littlest children.”

It appears from his book that Sam’s life was exactly this. But rather than complain, he treasured it.

***

The first half of Everything But Money is a love letter to Sam’s parents and siblings that roams between poignancy and hilarity. And like much of Jewish humor, it’s playful, satirical, and grounded in reality.

Levenson writes with a chuckling fondness about the ways in which his family dealt pragmatically with their paucity of funds. They couldn’t afford a doctor, for example, so when the kids were sick the best course of action was a decidedly nonmedical one:

Any remedy that made you perspire was good. “Try and perspire, Sammy.”

(My Italian father, by the way, also had a deep affection for the benefits of perspiration!)

And speaking of sickness, Levenson recalls that:

One of the classic stories of that era – one that has survived to this day – was about the mother who bought two live chickens. When she got home she discovered that one of the chickens was sick. She did then what any woman with a mother’s heart would do – she killed the healthy chicken, made chicken soup, and fed it to the sick chicken.

Another workaround involved the kids’ attempts at bringing “nature” into their homes, even in a tenement neighborhood:

Each spring we would write to our congressman for free seeds, which we planted in soil in cheesebox flowerpots. We called it soil but it was really a mixture of broken glass, gravel, decayed wood and mud that we found around construction projects. . . . I came home from school one day with a narcissus bulb that my teacher had given me. I left it on the kitchen table and went out to play. On my return I discovered that a visiting uncle had grated it and was eating it with sardines.

But here’s my favorite passage:

One of Mama’s favorite techniques was comparison – impossible us versus some paragon of elegance. “Does President Coolidge hang his dirty sock on a doorknob? Answer me! Does Rudolph Valentino leave his sneakers on a bed? Answer me! Does Chaim Weizmann chew his tie? Does the Prince of Wales throw newspaper into his mother’s toilet bowl?”

I’d like to use this on my dog.

“Buster, does the Dalai Lama spit out his medicine? Answer me! Does Tom Hanks feel a need to pee on every post? Answer me! Does Kate Middleton bark out the window for no apparent reason?”

This book is steeped in Levenson’s unwavering affection for his family. The overall message is that family love, and an upbringing that emphasizes honor and virtue, are what create happiness, whether one grows up in poverty or in wealth. “A good home,” he writes, “is defined as one in which there are love, acceptance, belonging, high moral standards, good parental example, decent food, clothing, shelter, spiritual guidance, discipline, joint enterprises, a place to bring friends, and respect for authority. Today any child, rich or poor, who lives in such a house is considered a ‘lucky kid.’ I was a ‘lucky kid,’ not in spite of my house but because of it.”

That’s where his comedy came from. A home without material plenty can be rich, instead, with humor. Italian funnywoman Joy Behar, for example, says that she wouldn’t be a comedian today without the lush material gleaned from her tenement life in Brooklyn.

The second half of Everything But Money takes a turn and covers Levenson’s serious didactic takes on education, child discipline, morality, etc. I agree with most of what he says, but the humor isn’t there, except for this gem:

Peaceful coexistence can be as strenuous for a child as for an adult. My little girl, Emily, came home from school one day in a state of near exhaustion: “All day long, sharing, sharing, sharing.”

***

By the way, as a complete digression, my all-time favorite excerpt from a comedian’s book comes from Billy Crystal’s Still Foolin’ ’Em.

“So I’ve tried everything to fall asleep,” Crystal says. “Then I got one of those sound effects machines that creates the experience of being on the beach. My model is called Coney Island. It has waves, weeping Mets fans, and gunfire.”

Billy Crystal is Jewish. I rest my case.

***

The paternal side of my family is Italian. There seem to be commonalities between Jews and Italians – mostly around the importance of family, food, tradition, and ritual. (And lots of loud conversation.) During Sam Levenson’s youth, when New York was the primary immigration hub in the country, Jews and Italians lived meagerly in similar neighborhoods and shared kindred struggles and cultural values.

Recent research may have uncovered a scientific basis to some of these connections. According to the Genetic Literacy Project, a 2000 study found that “most modern Jews are descended on their male side from a core population of approximately 20,000 Jews who migrated from Italy over the first millennium and eventually settled in Eastern Europe.” The paternal lines of Roman Jews, said the study, were similar to those of Ashkenazi Jews. While some experts dispute this, the Genetic Literacy Project notes “an emerging consensus” that “wandering Jewish men, from the Near East, established a mosaic of small Jewish communities – first in Italy.”

Put more colloquially, as comedian Sebastian Maniscalco says, Italians and Jews are “same corporation, different divisions.”

Or, as the old joke goes, Italians are just Jews with sauce.

***

My aunt Nini (real name Maria) and uncle Ray owned a small 1929 Spanish-style stucco house in San Leandro, California, in a neighborhood that was almost exclusively Italian and Portuguese. Their house was magical to me because it had a dining room, a front porch, and, most entrancing of all, a basement. When we were a young family, my father would drive us up from San Jose every other weekend to visit them and my grandparents, who lived two blocks away.

Because my aunt was almost 19 years older than my father, she and my uncle were grandparent-age. They were married when my dad was a toddler. But Nini had a timeless Mediterranean beauty, with a full head of wavy black hair that never fully turned gray. It was rare that I saw her without an apron, yet she always looked glamorous to me – often in a dress and fancy earrings and pearls.

Uncle Ray worked with my grandfather in a poultry market up the street. Aunt Nini – like most 1950s wives, at least in that neighborhood – raised children, kept up the house, and cooked. Boy, could she cook. She rolled out her own homemade pasta in that enchanting basement, and to this day I’ve never had ravioli as delicate and delicious.

Nini was short, but very, very loud, with a voice that could skin a cat. She was a tremendous prude and was constantly admonishing her husband, who had a proclivity for telling dirty jokes even though we kids were around. “Ray! RAY!!” she’d holler, not more than a couple of feet from anyone else in the room. “Stai zitto! Shut up! The ceiling is low!”

Most of the time we didn’t understand the jokes anyway, and “the ceiling is low” was an even bigger puzzle. What she meant was that “children are in the room.” But I’ve always thought that “the ceiling is high” would have made more sense. Wouldn’t the ceiling seem high to children?

I can’t say that my aunt struck me as a particularly warm woman; she was somewhat stern, like my grandmother. But she had a lot to say, sprinkled at times with a tinge of mischief. And she was extremely funny – often unknowingly. She used to tell us, for example, that she was “born dead.”

(I think she was just referring to her needing a few seconds to start breathing after birth.)

When she and Uncle Ray once went to a professional basketball game, her review of it was simply, “All they do is run back and forth, back and forth – those poor fellows.” She had an opinion, too, about the ways in which Italian Americans could misuse the English language. “They sling it,” she told me. I finally figured out that, ironically, she was using “sling” as a verb form of “slang.”

My observation is that Italian humor, unlike Jewish humor, is often inadvertent – at least among amateurs. Comedian Joy Behar, who’s full-blooded Italian (“well, Ancestry says only 92 percent,” she claims, “but what the hell is a Caucasus anyway?”), also describes growing up with Italians who were inadvertently hilarious. Her mother’s friend Caroline, for example, when asked why she didn’t move to Florida in her older years, replied, “Because I am not a water individual.”

Joy’s aunt Rose, like my aunt Nini, would cook huge family meals – soup, salad, antipasto, fritto misto (battered seafood and vegetables), ravioli, and then the main course. One day Rose woke up as if she’d had an epiphany and declared, “No more soup!” Then for years she’d tell the neighbors, “We don’t eat as heavy anymore.”

***

On January 1, 1958, my parents hosted a little party in our San Jose home for my grandparents’ 50th anniversary. Nini and Ray were there, too, along with their two sons. My father had turned on a wire recorder and surreptitiously set it near the table. (These recorders preceded tape and actually captured the sound on very thin steel wire.) Much of the time, the spool of wire would end up as a snarled, unsalvageable rat’s nest. But a few of ours didn’t, and luckily I had the foresight to take them into Radio Shack in the 1970s and have them transferred to tape.

What a treasure!

The recordings from that day reveal mostly an unintelligible, piercing riot of voices. One of the most prominent voices is actually mine; I was a toddler, obviously sitting near the recorder and asking repeatedly what it was. I must have asked 10 times, with no one paying attention over the din, my voice growing louder and louder until I was screaming in frustration.

“Come fa, Babbo? Come fa, quello lì? COME FAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA???”

(“What is that thing over there doing, Daddy?” I spoke only Italian in those days.)

I was ignored, of course.

At one point my father read a poem he’d written (in Italian) about his parents’ marriage. It was both poignant and funny. At the end my aunt proclaimed, “That’s so goooood! You should send it in!!”

Where was he supposed to send it?

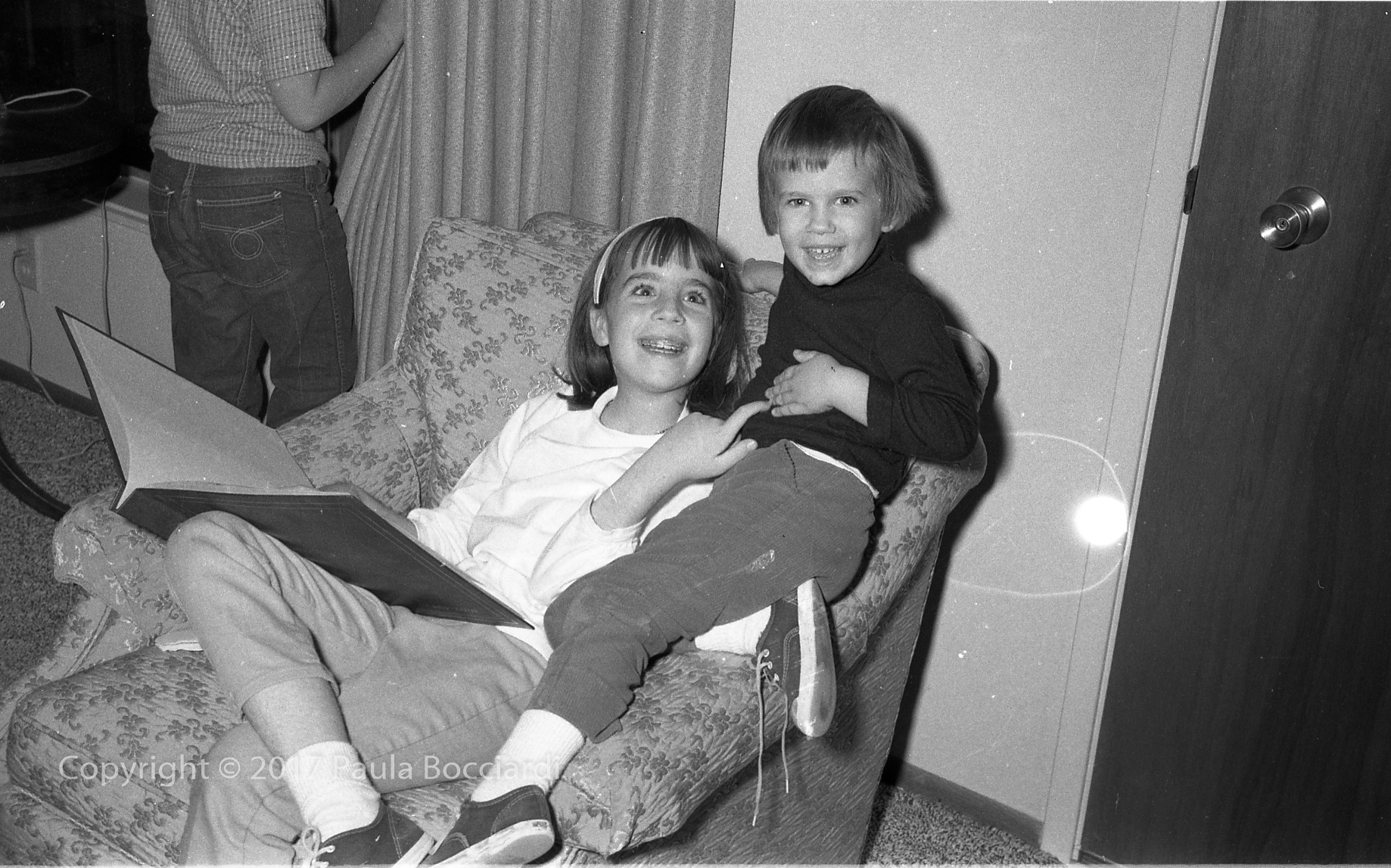

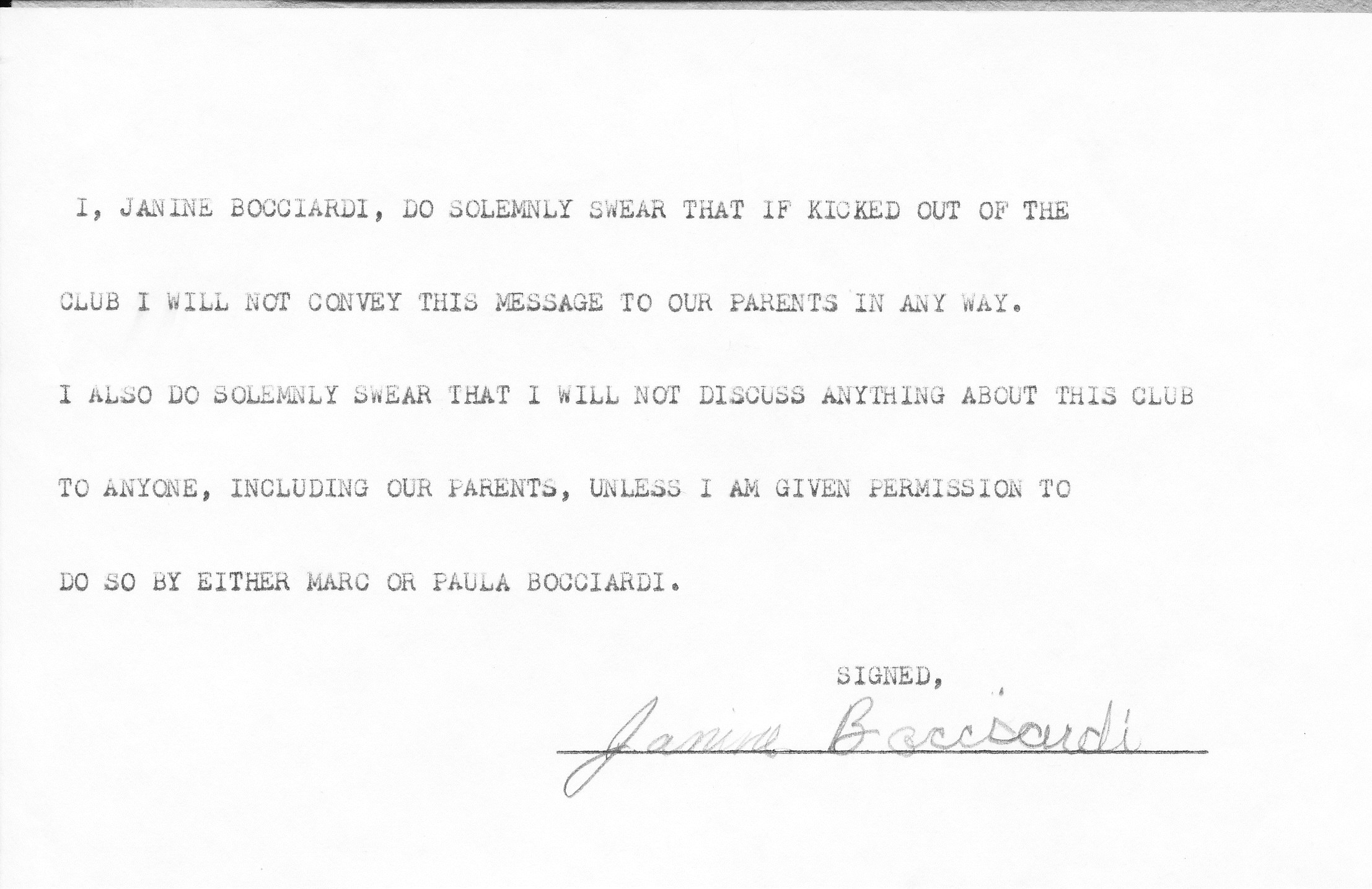

That line has remained with my siblings and me to this day. “Janine, your handmade card is so creative and beautiful. You should send it in!” Or “Your chicken cacciatore enters the realm of the godlike. You should send it in!”

Maybe that’s what we should be doing this Christmas: telling our loved ones that they’ve done something wonderful, and that they should send it in.

In any case, it was towards the end of the party when Nini really stole the show.

People were talking noisily about amore and kissing, and Ray had been telling a few of his slightly bawdy jokes, when his teenage son Dennis piped up.

“Ma! In 16 years, I haven’t seen you kiss Daddy on the lips yet.”

To which Nini promptly responded:

“What do you think I am, a MOVIE STAR?”

***

COMMENTERS, PLEASE NOTE: WordPress is no longer supporting my particular page type and doesn’t seem to be asking commenters for their names, so everyone is identified as “Anonymous.” If you’re commenting (which I love!), please leave your name if you’d like me to know who you are!

***

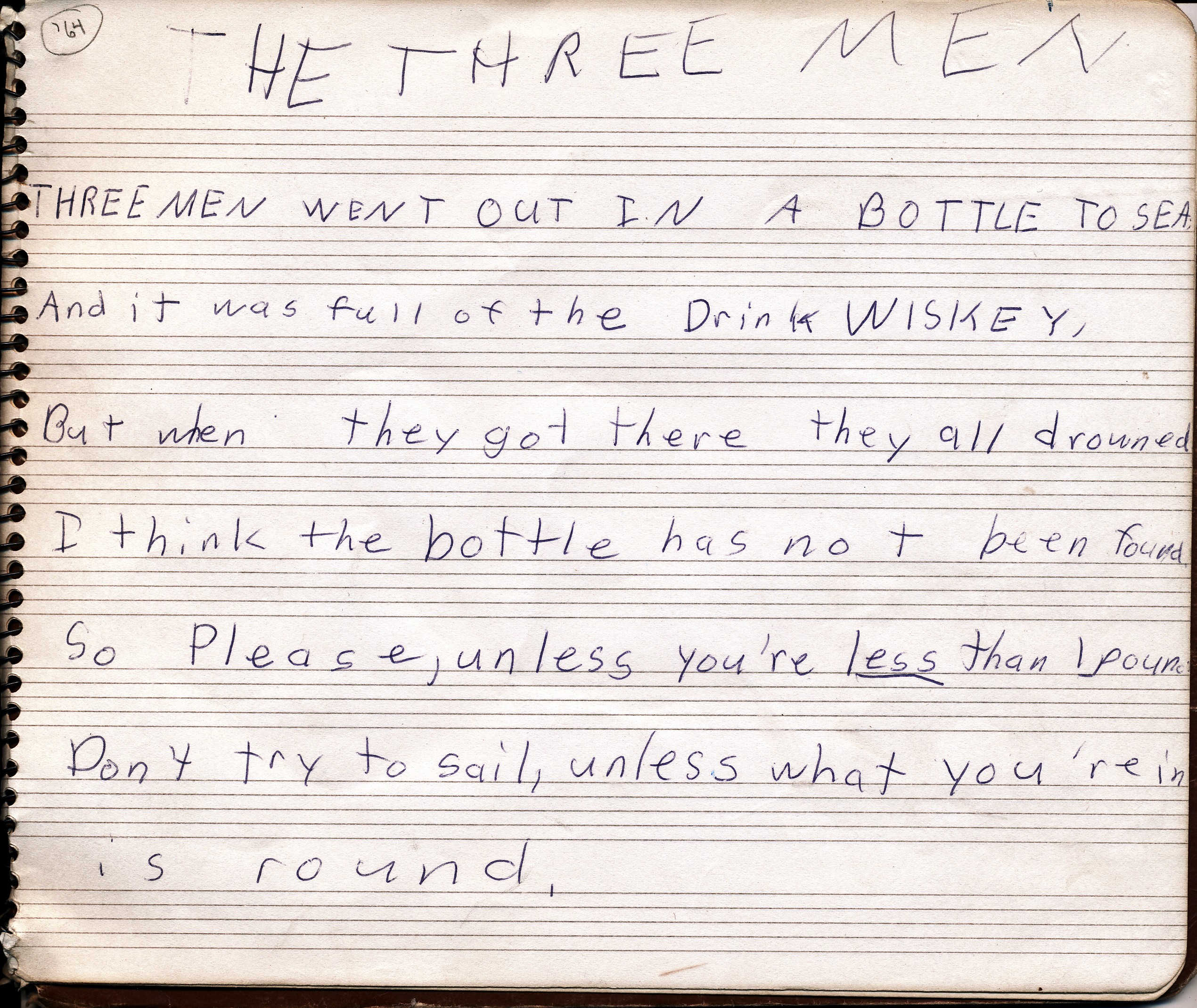

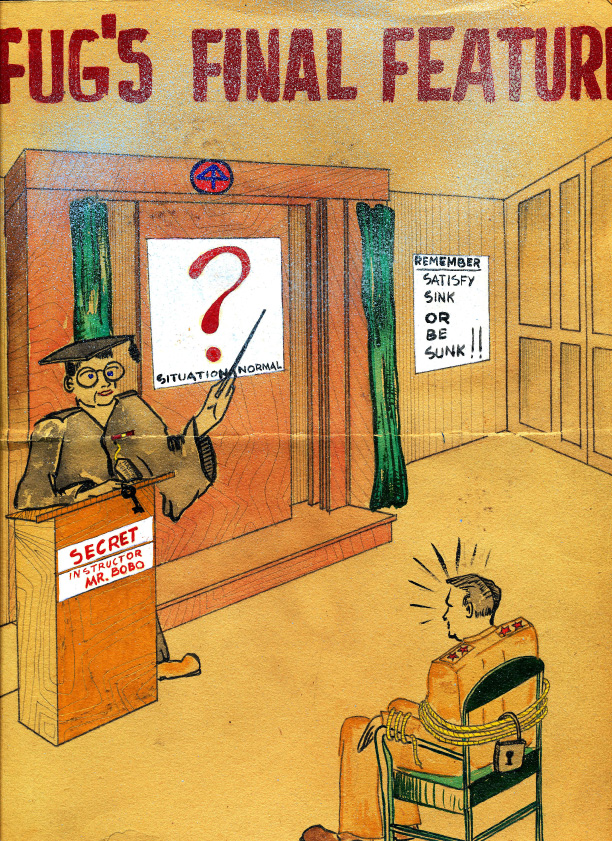

Due to popular demand, I am including, at the end of each blog post, the latest random diary entries that I’ve been posting on Facebook for “Throwback Thursday.” These are all taken absolutely verbatim from the lengthy diaries I kept between 1970 and 1987.

December 1, 1975 [age 20]:

“I just wrote a really long letter to [my friend] Jeanne [in South Carolina], and I realize now that everything was ‘I, I, I’ all the way and it was terribly egotistical of me. I’m thinking now that my missing her so much might be just a result of my own selfishness, because she reinforces me all the time with her praise. I DO think of everything in terms of myself (but then again, doesn’t everybody?). I suppose I’ll try to be more humanitarian from now on if I can, and not so selfish. What a terrible revelation about myself! Aak, I can’t stand it! I hope she doesn’t think too badly of me. I’ll have to send an apologetic postcard.”

December 5, 1975 [age 20]:

“[My brother] Marc and [my friends] Joe and Ted came to the dorms today and inspected my ‘Playgirl’ magazine and said it was the grossest thing they’d ever seen. Weird – it’s okay for men to look at these things but not women. Baloney!”

December 10, 1975 [age 20]:

“I’m [my dormmate] Mike’s Secret Santa and today I gave him a note written in anagrams. (Dear future Paula: That means ‘scrambled words.’ I have a feeling my intellect is going to dwindle as the years go by.)”

December 13, 1975 [age 20]:

“Today I went to Berkeley to do research for my Film final, which is getting to be a pain in the neck. I somehow made it up on BART, caught a bus in the freezing, driving winds up to campus, and smiled all the way to the library. God! I want to go to Berkeley instead of San Jose State! Oh, if only I could go! I’d learn so much from the atmosphere alone – absorb it right into myself. I KNOW they’re all brilliant – everyone I heard talking was. Besides, all the guys had curly hair and workshirts.”

December 14, 1975 [age 20]:

“It was so painful writing my Film paper today because while walking by Mom’s chest of drawers I caught my finger on a handle and kept walking while a piece of my finger stayed on the handle.”

December 19, 1975 [age 20]:

“I watched Abraham’s story of ‘The Bible’ on TV and it was so full of faith that it practically made me repent right there.”

December 27, 1975 [age 20]: [WARNING: get out your violins and your eyerolls]

“1975 has been the year of the void. It passed by shrouded in the hypnotic boredom of duty. The first half of the year I worked continuously and the second half I spent much of my time curled up in my [dorm] room trembling at the sounds of passers-by. I’m not sure I’m going to survive this awesome grief for the past. I feel guilty about drinking and I need to start going to Mass again. At any rate, I’ve got a future I’ve got to start thinking about. To teach or not to teach. To be a cop or not to be a cop. I’ve got to make some kind of decision soon. Meanwhile, it’s the old sweet touching of pen to paper for me. Music. Novels. And all I want to do is set forth something into immortality, create some piece of magic that’ll live longer than me. And maybe help someone else live better.”

December 28, 1975 [age 20]:

“A nice, sleepy drive down to L.A. today listening to my cassettes of Bob Dylan and the Byrds. I feel so grotesque, looking at my gorgeous cousins and sister. Sometimes I wonder if I’m really a lady after all.”

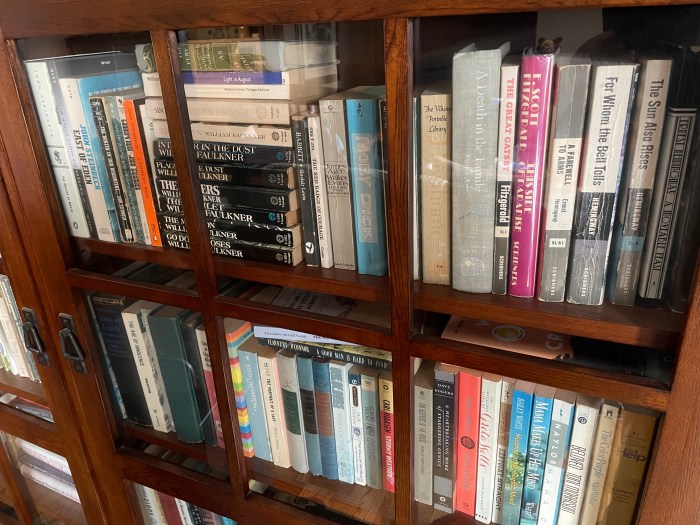

![IMG_1660-[edited for blog]](https://mondaymorningrail.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/img_1660-edited-for-blog-e1526874283221.jpg)

![IMG_1661-[edited for blog]](https://mondaymorningrail.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/img_1661-edited-for-blog.jpg)

![IMG_1659-[edited for blog]](https://mondaymorningrail.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/img_1659-edited-for-blog.jpg)