A few weeks ago, the Chronicle’s outdoor writer Tom Stienstra published a column that was a real blockbuster for me: one of Black Bart’s hideaways may have been discovered in the Sunol Regional Wilderness.

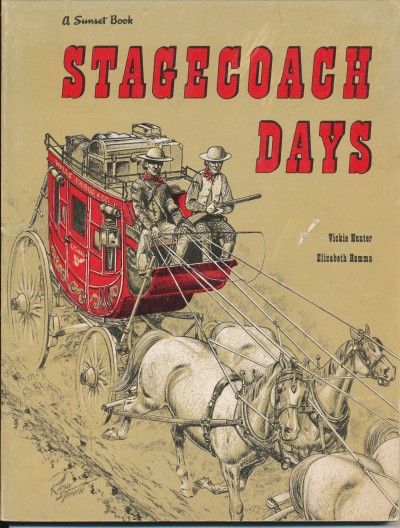

I was about 7 years old when I first learned about Black Bart in a thin little book called Stagecoach Days, a Sunset publication that Wells Fargo Bank gave away to its customers. A few years later, when I frequently insisted that my younger sister and I “play school” and that of course I be the teacher, Stagecoach Days was one of my two “textbooks.” (The other was the Bible. The sole reason I chose them was that they were the only books in the house of which we had two copies.)

Black Bart was an outlaw who robbed stagecoaches in the late 1800s, shortly after California’s great Gold Rush. I became obsessed with him for a couple of reasons. First of all, he was a “gentleman bandit” of sorts. Second, he was known to have left poems at his robbery sites, and one in particular became part of my repertoire. As a youngster and a bit of a loner, I took to memorizing things, and I could recite the states and their capitals, all three stanzas of “O Captain, My Captain,” the last two paragraphs of The Great Gatsby, assorted Kerouac quotes, and the entire Gettysburg Address. But my favorite piece of literature that I committed to memory was one of Black Bart’s poems. You’ll have to wait for it.

***

Born in England in 1829, Charles Boles (later Bolles, or Bolton, depending on his alias du jure) emigrated with his family to America when he was two years old. Not much is known about his childhood on a farm in upstate New York, but we do know that as a young man he and his brothers joined everyone else and their brothers in heading to California for the Gold Rush of 1848, hoping to strike it rich. Some were fortunate, but many came up empty. The Boles Brothers were in the latter group. They made two unsuccessful trips, and two of his three brothers actually died in California.

We also know that Charles fought with the Union Army during the Civil War, marching with Sherman through Georgia and suffering life-threatening abdominal wounds at the Battle of Vicksburg. Though his wounds were considered to be so bad as to preclude his ability to continue fighting, he rather heroically went back and served on the battlefield for three full years before being honorably discharged.

Charles eventually married and raised four children in Illinois and Iowa. But it seems that his stint in California had created in him an unshakeable urge to gamble, and he periodically would leave his family to mine for gold, at first in Montana and Idaho and eventually back in California. During this period he sent his wife a letter, recounting an event in which Wells Fargo agents tried to buy out his share of a small mine he was tending in Montana. When he refused, apparently the bank agents somehow cut off his water supply, forcing him to abandon the mine. His conviction that he had been wronged caused him to tell his wife that he was going to “take steps” to exact revenge. The poor woman never saw him again, and at this point she just assumed that he had died.

But he hadn’t. And gold fever still infected his bloodstream, so he headed back to California with one last hope of striking it rich.

***

In those days, stagecoaches were often used to transport passengers, mail, and valuables to and from areas not served by the railroad. Enterprising robbers realized that they had a convenient opportunity to simply travel to areas through which they knew the stage would be passing and quickly hold up the helpless driver and passengers without leaving a trace. They often would select a spot through which the stage would be traveling laboriously – e.g, up a steep hill – and spring out from the bushes, brandish their rifles, demand the loot, and scram out of there in very short order. The greatest bounty they could get was the box of money that companies like Wells Fargo transported to pay the workers who labored in their mines.

During the period 1870 through 1884, there were 313 attempted robberies of Wells Fargo stagecoaches. Wells had the money to hire some very accomplished detectives, though, who did a fairly good job of solving these crimes. Five miscreants were killed during the attempts, 11 were killed resisting arrest, 7 were hanged by lynch mobs, and 206 were ferreted out and sent to jail. Only 84 robberies were “unpunished,” but many of them, it turns out, were committed by the same person.

***

During this time, Charles Boles was living in San Francisco. He lived a rather highbrow life despite not necessarily having the means to do so, since all he appeared to own were some unsuccessful mining interests in the hills. He attended the theater and concerts, ate at the finest restaurants, wore natty clothes, and always sported a cane. The cane was fashionable rather than functional; he was in terrific shape, walking many miles a day. He reportedly never took a drink in his life, always carried a Bible with him, and was generally a respectable, quiet man who eschewed profanity and was not prone to any kind of excess other than his unending tendency to take a gamble.

During this time, Charles Boles was living in San Francisco. He lived a rather highbrow life despite not necessarily having the means to do so, since all he appeared to own were some unsuccessful mining interests in the hills. He attended the theater and concerts, ate at the finest restaurants, wore natty clothes, and always sported a cane. The cane was fashionable rather than functional; he was in terrific shape, walking many miles a day. He reportedly never took a drink in his life, always carried a Bible with him, and was generally a respectable, quiet man who eschewed profanity and was not prone to any kind of excess other than his unending tendency to take a gamble.

***

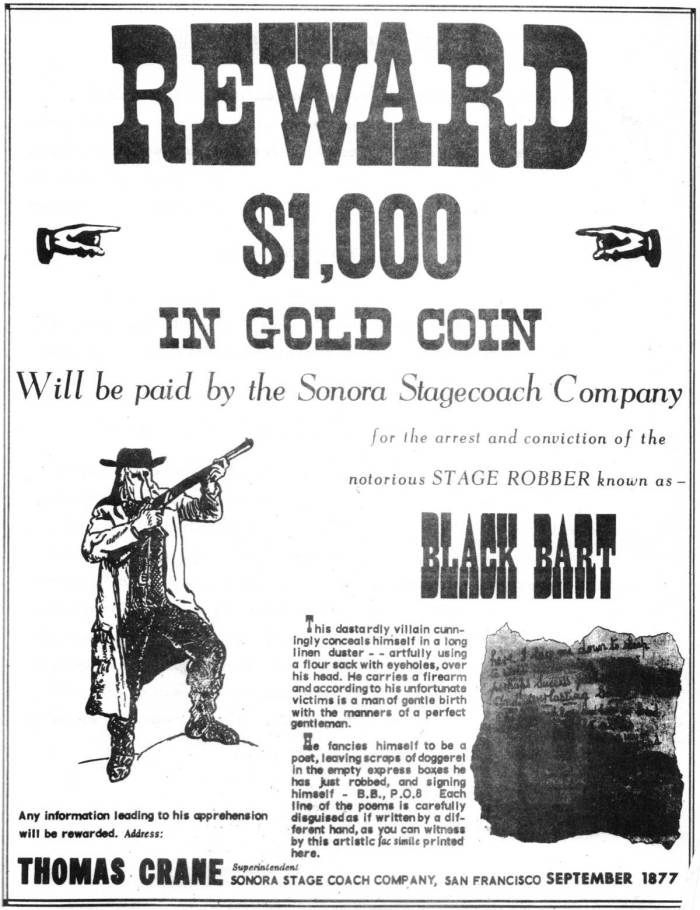

Beginning in 1875, Wells Fargo stagecoaches traveling through California’s Gold Rush country would be hit 28 times by the same bandit. Some say he was afraid of horses and others say he simply couldn’t afford one, but in any case he walked to and from his crimes and carried a shotgun that he never fired, which was a good thing because it was so rusty that no bullet could have successfully traveled through its muzzle. He wore a flour sack with two holes cut out for the eyes, and he sported a linen duster (which is a long coat). Unfailingly polite, he never harmed a passenger; in fact, if they handed over their money or jewelry, he would insist on giving the items back to them. All he wanted was Wells Fargo’s money. And he was highly successful, netting thousands of dollars a year.

For me, though, the most delightful thing about the bandit was that on a couple of occasions he would leave poems at the site, like this one:

Here I lay me down to sleep

to wait the coming morrow;

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat

and everlasting sorrow;

Let come what will, I’ll try it on

my condition can’t be worse

and if there’s money in that box

’tis munny in my purse

— Black Bart

Black Bart was the name of a fictional character who had appeared in a story called “The Case of Summerfield” that ran in the Sacramento Union in the early 1870s. That man, though, was a vicious villain and certainly didn’t resemble the gentleman who was robbing these stagecoaches. But the name sounded ominous, and the robber didn’t mind the fear it instilled in the public. He probably also thought the moniker would evoke an image that was such a far cry from his public persona that it would throw detectives off the trail.

The story goes that at his first holdup, in July 1875 in Calaveras County, Black Bart asked the driver to please “throw down the box” and shouted over his shoulder into the woods, “If he dares to shoot, give him a solid volley, boys.” The driver, on seeing several rifles pointed at him among the trees, swiftly threw down the box as ordered. Then, after the bandit disappeared, the driver discovered that the rifles in the woods were just meticulously crafted sticks.

It was at the scene of his fifth crime that Black Bart left the poem that I have memorized, and it makes me smile every time I repeat it (bear in mind that Stagecoach Days conveniently did not include this particular poem):

I’ve labored hard and long for bread

for honor and for riches,

But on my corns too long you’ve tread,

you fine-haired sons of bitches.

***

Black Bart committed his last robbery on November 3, 1883. A man with one of the greatest first names in the world – Reason McConnell – was driving a stagecoach out of Sonora alongside a 19-year-old boy named Jimmy Rolleri, who had just been gifted a new rifle and was out to do some rabbit hunting. At the bottom of a place called Funk’s Hill, Jimmy jumped down from the stage to look for rabbits and Reason continued up the incline. Black Bart leaped into the road at the summit and, as was customary for him, politely asked for the express box, which was bolted to the floor in an attempt to thwart such robberies. When Reason pointed out this situation, he was ordered by our robber to step down and unhitch the team, at which point Bart himself jumped up and started working on the box with a hatchet. Meanwhile, Reason slipped away and got Jimmy’s attention, and somehow three or four shots were then fired at Bart with Jimmy’s new rifle. The local newspapers reported that the driver had fired all the shots, but Jimmy’s family members insisted that after Reason missed the first two, Jimmy disgustedly snatched the gun from him and slightly wounded the bandit in the hand. (Apparently there is some evidence that Wells Fargo later gave Jimmy a fancy inlaid and engraved rifle.) In any case, only one of the shots grazed Bart, who took the $550 in gold coins and 3-1/4 ounces of gold dust worth $65 and got clean away.

Or so he thought.

Wells Fargo detective J.B. Hume was quickly dispatched to the scene, and there he discovered a black derby, magnifying glasses, field glasses, and a handkerchief, among other things. And in one corner of the handkerchief was a laundry mark.

Ultimately, Detective Hume and his associate Harry Morse traced the laundry mark to San Francisco and, after visiting 90 laundries, finally learned that that particular mark was used by a fine gentleman named C.E. Bolton. Mr. Bolton took frequent trips into the hills to check on his “mining interests,” but he always came back to his boarding house in San Francisco – which, by the way, was directly across from the police station. In fact, he often dined with the gentlemen of the police force and expressed an acute interest in that nasty outlaw Black Bart.

Detective Hume filed this report:

“Bolton, Charles E., alias C.E. Bolton, alias Black Bart, the PO-8 [“poet,” get it?], age 55 years; Occupation, miner; Height 5 ft. 7-1/2 inches; Color of hair, gray; color of eyes, blue; gunshot wound on side. He is [a] well educated, well informed man, has few friends. He is a remarkable walker, has great strength, endurance.”

Charles pleaded guilty to the one crime and spent four years in prison at San Quentin. During that time he sent a number of letters to his wife, professing his love, expressing remorse for this crimes, and asking her for forgiveness. She apparently responded that she would be willing to take him back, but when he was released from prison, he vanished.

He was the most successful bandit in the history of the American west.

There are countless rumors, folktales, tall tales, old saws, fables, and fantasies about what happened to Charles after he was released. Three Wells Fargo stagecoach robberies took place shortly thereafter, but no one was ever caught, and there was no tangible evidence linking Charles to the crimes. In one story, however, Detective Hume somehow tracked him down and offered to pay him a lifetime pension out of Wells Fargo’s money if he would just, for the love of God, stop ripping them off. Some say he moved to New York City, where he spent his last days. Others speculated that he went back to Montana to try more mining. The most popular story seems to be that someone saw him boarding a steamer and heading for Japan.

***

So, who were the “fine-haired sons of bitches” to whom Charles directed his antipathy? His hatred probably didn’t emerge during his Civil War days; in researching this piece I learned that it was common among Confederate soldiers – but not among Union soldiers – to aim their sights at companies that appeared to have too strong on a grip on the economic machinery that ran the country. No, most likely it happened when the Wells Fargo agents used their power to unfairly force him off his own mine. So his particular grudge was probably against that one company. And perhaps the wealthy money-lenders could afford to keep their hair fine? I don’t know. Maybe someone can look that up for me.

I know that it’s wrong of me to harbor any feelings of admiration for a criminal. And just because he stole from a massively wealthy company does not mitigate the crime. I learned this early on from my mother. When I was in college, my friend Jeanne and I concocted a scheme by which we could talk endlessly to each other, long-distance, for free. In those days, of course, it cost a ton of money to make a long-distance call, and there was no way my parents would have paid the bill for such a luxury. (Plus they completely distrusted Jeanne because she wore wire-rimmed glasses.) But Jeanne was working as a telephone operator on the East Coast, and she had access to credit cards held by large corporations. So I would find a remote, unoccupied phone booth somewhere, and I would somehow place a call to her, through an operator, that allowed me, without charge, to give her the number on the phone in the booth. Then I would hang up and she would call me back using a random corporation’s credit card number.

As I type this, I am absolutely appalled at myself. But back then I thought that it didn’t matter because those big companies had unending funds and they would never miss the paltry amount it would cost them. I was so clueless about what I was doing that, in fact, I went home and cheerfully told my mother all about the scheme and how clever we were and that we would never get caught. Very calmly, but while undoubtedly choking back her complete disgust, my mother explained to me that stealing is stealing. It took all of two minutes for her to point my moral compass away from south and back to true north, where it has been ever since.

Still, I will always secretly admire California’s gentleman bandit, and I will forever appreciate the way in which he poetically told those fine-haired sons of bitches that they had stepped on his toes for far too long.

Hello mate great blog postt

LikeLike

I have this book. It was my great grandfather’s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re making me feel old! Ha ha

LikeLike

Hey Miss P- Loved it! Loved it! Loved it! Keep them coming! Yes Janet, I did not know of this BLACK MARK either. A tad shocking I do say. We are learning more and more about Paula, and dear Bev of course too. ML

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was wishing for a newspaper this morning to read in bed with my Joxer boy snuggling and Jill away…… but no paper is delivered and another story I did find — thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’re referring to our classmate Jean A. Always wondered what became of her. PM me if you have more info, please!

LikeLike

Fascinating as always! Thank you for making Monday mornings so enjoyable. The cbs Sunday morning show needs you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, between your criminal days of long ago of pilfering from large corporations and my criminal days of yore “borrowing” horses, we could probably rustle up the beginnings of a gang called “Black Barbara”, or similar……. Bwahahahahahaha!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Speaking of rustling, it sounds like you were a modern-day horse rustler!

LikeLike

Paula, I love this folkloric tale of Black Bart and your confession of your own short-lived crime spree nipped in the bud by your mother’s gentle remonstrances. Obviously, left to your own inclinations, your moral compass swings widely!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice story! Politicians have been robbing from us for years and Wells Fargo too!!! Leon

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Paula, I enjoyed your very interesting article on one of the notorious characters of the Wild, Wild West. Your comments are, as usual, clever and made me giggle. When you have a few minutes, please dig up the song “Black Bart” by one of my fave bands Volbeat (from Copenhagen, of all places — I’ve seen them live and they ROCK!). The album is called “Outlaw Gentlemen and Shady Ladies” (totally fun name and rockin’ album). You may enjoy the lyrics! Thank you for sharing this piece. I’ve often found myself romanticizing about the Old West. I would have enjoyed wearing the girly fashions from that period. “Tombstone” may be my very favorite movie of all time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anonymous! Rats… those comments are from LORI D! Oopsie!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, Lori, I had no idea that this song existed! Or that this band existed, for that matter. (I like an alt-country band called the Volebeats out of Detroit, and at first I got them mixed up.) I listened to the song and read the lyrics and they capture much of what I mentioned in the blog! It’s so interesting that a band from Copenhagen would write about American outlaws. You are a true metal rocker!!! And thank you for identifying yourself. Before I saw your second reply I was tearing my hair out trying to figure out who this heavy-rockin’ girly-fashion person was!!!

LikeLike

Interestingly, there is an expression, “as fine as frogs hair,” meaning that a criminal had escaped and is free…I wonder if he meant that the Wells Fargo people who stole his mine had gotten away with a criminal act?

And hey, I’m all for Black Bart. First, because I learned to read with him (with the best teacher ever), and second because Wells Fargo still has shady practices. I pulled my money out of there years ago, after working for them for a few months and discovering how they treated their employees and customers. Go, Bart!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, I love your interpretation of “fine-haired”! It makes a lot of sense. Thank you for the fine research!

LikeLike

Paula, Paula, Paula… I had no idea you had this black mark on your record! I also didn’t know the story of Black Bart, a romantic fellow through and through.

LikeLiked by 1 person